Twitter was a fumin’ over the last few weeks in response to author Lionel Shriver’s controversial keynote address at the Brisbane Writers Festival. Her speech meant to discuss “community and belonging,” quickly dissolved into a tirade against the rampant (and completely imagined) “crisis” plaguing white authors today: political correctness.

…I’m afraid the bramble of thorny issues that cluster around “identity politics” has got all too interesting, particularly for people pursuing the occupation I share with many gathered in this hall: fiction writing. Taken to their logical conclusion, ideologies recently come into vogue challenge our right to write fiction at all. Meanwhile, the kind of fiction we are “allowed” to write is in danger of becoming so hedged, so circumscribed, so tippy-toe, that we’d indeed be better off not writing the anodyne drivel to begin with.

But this latest and little absurd no-no is part of a larger climate of super-sensitivity, giving rise to proliferating prohibitions supposedly in the interest of social justice that constrain fiction writers and prospectively makes our work impossible.

While Shriver isn’t a children’s fiction writer, I’m going to quickly take the conversation there, as her words struck a definite nerve in the community, and is certainly a reflection of everything that progressive publishers, authors, and readers are fighting against – the serious lack of equal representation in children’s books. But first, I can’t stop myself from responding to just a few of Shriver’s comments.

- To imply that your intellectual freedom as a fiction writer is being impinged by the concept of cultural appropriation is absolutely ridiculous. In fact, it would hinge on the farcical if this entire conversation were so completely not funny.

- No one is demanding authors “get permission” to write POC characters. What they are demanding is that when you do write characters of different racial and ethnic backgrounds from your own, you do it well, and you write those characters with an authentic and sympathetic voice. READ: Not under the cloak of long-held, harmful, and culturally offensive stereotypes. Research must be compiled, interviews conducted, and sensitivity readings done. This doesn’t make the final product “circumscribed” or “tippy-toed”. It means you actually did your job.

- As far as Shriver’s comment that we’d “be better off not writing the anodyne drivel to begin with,” I think that the hugely disproportionate number of underrepresented readers would disagree.

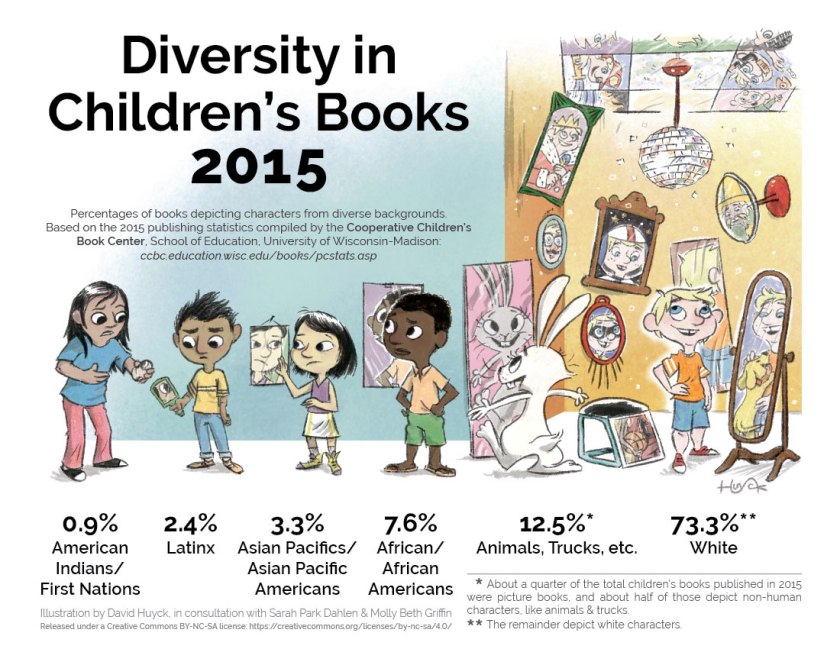

The Cooperative Children’s Book Center recently published an infographic that does a great job showing the disparity of representation in today’s literature for children:

In 2015, the number of books by/about people of color came in at around 14% (up from 10% in 2013) of the 3,000 to 3,500 books the CCBC reviews each year. While white readers are allowed to see unlimited reflections of themselves in the books they read, POC readers are severely limited. This is damaging for a myriad of reasons, the simplest being that children deserve to see these reflections, they deserve to be more than a supporting character, and they certainly deserve more than to be written as a harmful cultural stereotype.

Author Dhonielle Clayton writes about the effects this kind of representation had on her own childhood and sense of identity as a young black girl growing up in Washington D.C.:

As an adult looking back, I realize now that my discomfort came from the fact that I couldn’t find myself. I was always the sidekick in books, movies, and TV. Girls who looked like me never got the guy. Seventeen magazine gave tips for the latest hair trends, but they never included my hair texture. I was always pretty for a black girl. I was the smudge.

As a young white reader, I never saw myself as “the smudge.” Finding representations of myself in books and media was as simple as pulling a book at random. I know now that this isn’t fair, and while I’ve spent the majority of this blog post attesting to that very fact there is still much I need to work on. While I sit here, discussing the great need for diversity in literature for young readers, I must also take some of the responsibility.

This sentiment was never more apparent to me than when I decided to take stock of my own shelves. I began thinking about my book collection and how many POC characters and #OwnVoice authors were represented. So, I sat down and counted. And honestly, I’m a bit ashamed at what I found:

Number of Children’s/YA Books: 135

Number of Children’s/YA Books by #OwnVoice authors or with POC characters: 11

With numbers like these, I have officially become part of the problem. I can like, write, and promote blog posts about diversity in children’s fiction all day, get angry at comments by authors like Shriver, and shake my head at the unfairness of it all until I pass out from dizziness. But I also have to support the literature that is already out there.

And this is my pledge to do just that.

Support #OwnVoice authors. Buy their books if you have the funds and check them out of your local library if you don’t. If your library doesn’t have them (like mine didn’t), request them. Read, review, share, and promote them. I haven’t been – but I will now.

Resources and Links

There have been many excellent responses to Shriver’s speech (each much better written, and more timely posted, than my own). Just some include this one by Yassmin Abdel-Magied, who was a member of the audience during Shriver’s speech and walked out. Others include a newly published article by author Jess Row, and a blog post by children’s book author and friend Ali Standish, writing from the perspective of an author trying to get representation right in her own books.

Blogs to follow for diverse book recommendations and discussion:

http://weneeddiversebooks.org

http://readingwhilewhite.blogspot.com

https://thebrownbookshelf.com

http://readdiversebooks.com